The golf world watched in rapt attention this past May at the PGA Championship as club pro Michael Block snuck through the cutline and hovered at the very top of the leaderboard, climbing as high as second place on the second day of play. They cheered uproariously when he aced the 15th on Sunday, and when he finished the tournament in 15th place, Block reported that he received hundreds or thousands of congratulatory messages, including one from Michael Jordan himself.

The way the popular narrative went, Block was barely more than an amateur golfer who managed to grind his way to one of the biggest stages in the world before his miracle weekend at the Oak Hill Country Club in Pittsburgh, site of the PGA Championship.

Of course, the narrative isn’t true. Not even close. Although Block isn’t a card-carrying member of the PGA Tour, he is far from an amateur. The 46-year-old holds five lower-tier professional wins, has played in 25 PGA Tour events, has seven appearances in major tournaments, and won the Southern California PGA Player of the Year award nine times out of 10 between 2012 and 2022.

Michael Block was certainly not a household name before his underdog run at the PGA Championship, but like so many journeymen who come through local and regional qualifiers to tee it up with the best in the world, he was far from being a nobody.

The narrative of the everyman golfer finding his place and holding his own during a major tournament has an undeniable allure. We all want to believe that given half-an-opportunity and a little bit of good luck, we’d swing in such a way that we felt we belonged in a pairing with Justin Rose or Rory McIlroy.

It sounds like a good story.

But the real story is better.

—–

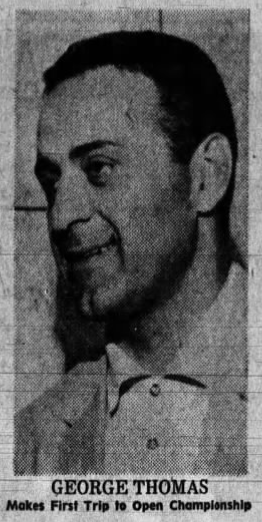

In 1966, Sports Illustrated ran a profile of an Indiana man named George Thomas called A Nobody at the Open. In 1965, Thomas was living in Michigan City, working as a golf pro by day, a pharmacist by night, and living as an aspiring PGA champion the rest of the time; chipping in the back yard, putting in the living room, and sneaking off to the course whenever he could. He was the perfect subject for SI writer John Underwood; Thomas had a day job and a family and had already tried and failed nine times to qualify for the U.S. Open before he turned 40.

In 1965, he would try again.

The first step was a local qualifying event at the South Bend Country Club. Over the course of two rounds, Thomas shot a 142. It was the best score of the event, and he moved on to a sectional qualifying event at Medinah Country Club outside of Chicago. Thomas called Medinah the toughest course he’d ever played, but managed to shoot a 148, good enough to earn his entry into the U.S. Open on his 10th try, six months after his 40th birthday. He was the first person from the Michiana area to find his way into the prestigious tournament.

A few weeks later, Thomas was at the Bellerive Country Club in St. Louis getting in his practice swings and his practice rounds before the tournament started in earnest. It didn’t take more than a moment for the man to realize that he was well beyond the confines of his home course in Michigan City. When he stepped onto the driving range for the first time, he was hitting balls just a few yards from Jack Nicklaus. He played a practice round with Chi Chi Rodriguez and then another. On the day of the tournament, he shared the locker room with dignitaries like Arnold Palmer and Sam Snead.

Then the tournament started, and it was time for his heroes to stop being his heroes. Instead, they became his competition. Thomas got off to a rough start with a pair of bogeys in the first four holes before dropping a gorgeous 45-foot birdie putt on the 7th. After a run of pars, Thomas seemed to be in decent shape before suffering an implosion of bogeys toward the end of the round.

After Thursday, Thomas sat at 77 and would need a better Friday if he wanted to make the cut and see the weekend. It might have been disappointing, but there were bigger names in the tournament who’d also struggled on day one. Nicklaus shot a 78, one shot worse than the pharmacist from Elkhart. Palmer was at 76, just one stroke better. The Michigan City News-Dispatch ran the sensational headline the next morning:

Thomas, Nicklaus, Palmer Grouped

Thomas had predicted that it would take a two-day score of 150 to make the cut and play into the weekend, which meant he needed to be four strokes better on Friday than he was the day before. Through the first five holes, he was on his way, playing exactly even par.

Then he walked up to the 6th tee. A short par three flanked by a quiet pond, the hole seemed simple enough, but everyone knew that the water had swallowed 39 balls the day the before, even including one on a wayward putt. Thomas had stayed dry in the first round, but on day two, he found the water twice and ended up taking a seven. He pulled together a miracle run on the back nine, carding birdies on four out of five holes, but a bogey on the 16th doomed his chances. He shot a 75, finished with a 152 and missed the cut by two strokes.

It was little solace, but Thomas was in good company. Although Nicklaus had rallied with a good second round, Palmer had faltered and missed the cut as well, scoring a 152, placing him into a tie with George Thomas, the everyman pharmacist and soda jerk from Elkhart, Indiana. It marked the end of Palmer’s career as a major contender, but he would still run off another 39 professional wins in his career. As for Thomas, he was able to parlay his fame into a career as the club pro at the Elcona Country Club in Bristol and never scraped away the parking sticker on his windshield that called him a “contestant” at the 1965 U.S. Open.

Of course, that’s not the whole story.

George Thomas wasn’t a nobody, just like Michael Block isn’t a nobody. He certainly wasn’t some weekend hack who wandered onto the right golf course at the right time to rub shoulders with Snead, Palmer and Nicklaus.

The full story is that George Thomas was a Lebanese immigrant who found his way to America, placed into his high school’s athletic Hall of Fame, flew B-17 bombers for the United States during World War II, and landed at Purdue University as a scholarship quarterback who also made his way onto the golf team. He married Barbara and they raised five children together.

The full story is that the 1965 U.S. Open wasn’t Thomas’s only experience competing at the highest level. He’d qualify for the PGA Championship in 1974 and again for the U.S. Open in 1976, at the age of 51. George Thomas was a three-time Indiana PGA Player of the year, an inductee into the Indiana PGA Hall of Fame, and a record-holding seven-time Indiana Senior Champion.

The full story is that Thomas went on to become the golf coach at the University of Notre Dame. There he led his teams to six conference championships and was named coach of the year on three occasions. In 1999, he received honorary membership into the Notre Dame Monogram Club. When Thomas passed away in 2012, he was buried in Notre Dame’s Cedar Grove cemetery and the plot next to his was set aside for his best friend and most frequent golf buddy. When Coach Ara Parseghian died in 2017, they lowered him into the ground next to his old pal George Thomas.

It’s not a bad haul for The Nobody at the Open.