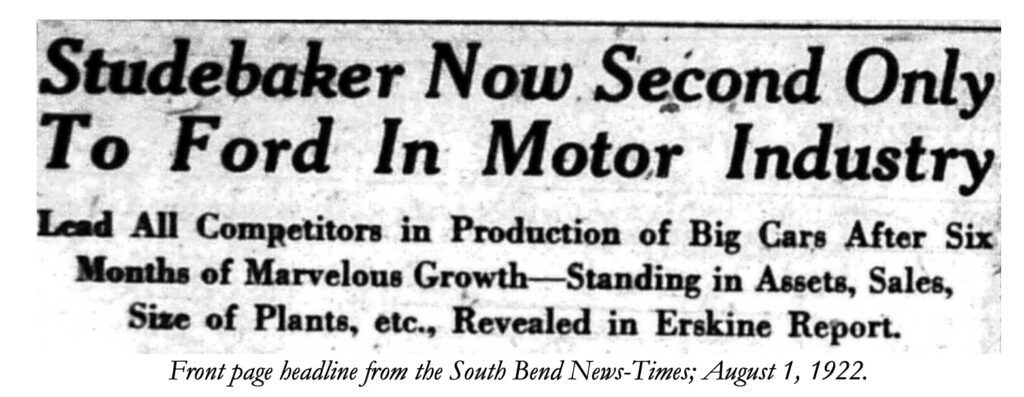

It was August 1922 when Albert Erskine made an announcement that sounded too good to be true, and in retrospect, maybe it was. The headline was gaudy, but Erskine, then president of The Studebaker Corporation, was somehow gaudier:

The South Bend News-Times had a front row seat to Erskine’s presentation, and called his speech a “romance in figures and in remarkable growth.” For Albert Erskine, who was famously prone to exaggeration when describing his own wealth and success, it might well have been a fiction.

Technically speaking, Erskine wasn’t telling an outright lie. Studebaker was second to Ford in cash assets. It was second to Ford in the cost and size of its plants. It was second to Ford in the “value of its sales,” a nuanced term that does not mean the same thing as net sales.

In the most important metrics – revenue, profits, market share, and cars on the road – Studebaker was doing well, but not quite as well as Erskine wanted the world to believe. Erskine’s announcement should have been lauded as a harbinger for future growth, but was treated instead as the moment when Studebaker had ascended to the top of some of corporate mountain.

Trouble was, there was still a lot of climbing to go.

It’s a small bit of poetry and something more than irony that one only needed to turn to the second page of the August 1 issue of the 1922 South Bend News-Times before being confronted by another headline and another news story. It turns out The Studebaker Corporation had a problem that required top-of-the-line professional help. An apocalyptic rat infestation had taken over their factory. Somewhere beneath the shiny veneer of Erskine’s triumphant proclamation and on the next page of the local newspaper, there was evidence that things weren’t as good as they seemed.

But that wasn’t going to stop Albert Erskine.

While Ford and its competitors were doubling down on consolidating their market shares and investing in research and development, Erskine popped the corks on the champagne. He announced an increase on the annual dividend that would be paid to stockholders, as well as a special one-time bonus dividend to be paid out the next month.

All of it was chalked up as a celebration of Studebaker’s success, but Erskine made it clear – this was a toast to the company’s president more than anything else. 1922 was the beginning of a trend, and for the better part of the next decade, Erskine would work harder to guarantee the esteem of his stockholders than the success of his company.

Erskine was the worst and purist form of an egoist. Among his first actions as Studebaker’s president were to name a model of car after himself and to publish a history of the corporation that lauded his own role far more than it deserved. He even made himself into the grandest patron of college football, naming the first college football national championship trophy after himself. It might have been good for his own self-image, but none of those invented accolades would be enough to save his reputation or his company in the long run.

The most important truth in Erskine’s 1922 statement was about Studebaker’s cash assets. At the beginning of the 1920s, Studebaker did hold more cash than any car company not named Ford. Those assets should have provided the great war chest they used to lay a foundation for the next 100 years of automotive greatness. Instead, Erskine raided those savings accounts immediately as part of a self-satisfying fiscal bacchanalia that would eventually spell the company’s downfall.

For his part, Albert Erskine was nothing if he wasn’t consistent. Studebaker would continue to pay some of the highest dividends of any auto manufacturer during the next decades, even through the leanest years of the Great Depression. By 1933, Studebaker’s record war chest was empty, the company was broke, and even though it would take another thirty years to shut the doors, Studebaker was spiraling toward insolvency.

Albert Erskine committed suicide on June 30, 1933; shortly after being removed from the presidency at The Studebaker Corporation.