My eyes were blurry and fuzzy, courtesy of a four-hour binge session in the microfilm room, a byproduct of a bizarre obsession I’d developed for a Babe Ruth home run that never even made it into the record books. In fact, I’d just spent the final hour of that session poring through century-old issues of South Bend’s Goniec Polski, a newspaper written in a language I don’t read, in order to find a photograph that wasn’t there.

That was just the beginning.

In fact, by the time I was done scrolling through microfilm, interviewing archivists, leafing through old maps, convening with librarians, and contacting individuals from around the country, I was left with a story, a history, and even a bit of a mystery.

It all begins with one of the most bizarre endings to a World Series in the history of baseball (and a collection of some of the greatest old-timey baseball names you could ever hope to read).

THROWN OUT TO END THE GAME

Babe Ruth’s 1926 season featured the kinds of gaudy statistics we’ve come to associate with the greatest slugger the game has ever seen. He led the league with 47 home runs and 153 RBIs. In fact, the only thing that kept the Bambino from winning the Triple Crown was his .372 batting average – somehow a full six points off of Detroit’s Heinie Manush.

It was a good season for the squad from New York, even though it would be another year before they’d truly become the Bronx Bombers. The Yankees raced to the A.L. pennant in 1926, led by Ruth, a young Lou Gehrig, and aging hurler Urban Shocker.

Once into the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, Ruth would continue his dominance, smashing four homers across seven games in a clash that would come all the way down to the wire. In fact, Ruth himself would feature into the closing moments of the World Series in a way that no player ever had before and never has since.

His Yankees were down 3-2 with two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning when Ruth drew a walk from Grover Cleveland Alexander, becoming the potential game-tying run.

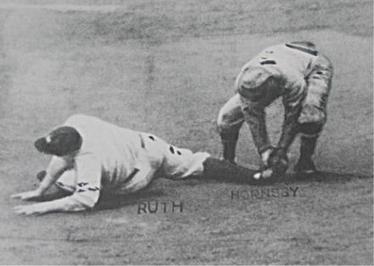

Ruth took his lead off of first base and watched for the signs from Manager Miller Huggins. The hit-and-run was on, and as Alexander moved toward home, the Babe was off toward second. Yankees outfielder Bob Meuesel issued a flail and a whiff at Alexander’s fastball and just like that, Ruth was hung out to dry. The throw from Cardinals catcher Bob O’Farrel found its way to Rogers Hornsby’s glove, and Ruth was tagged out to end the game, giving the Cardinals their first championship.

As for Babe Ruth, he wouldn’t have long to mourn the ending of the game.

After all, he had to get to South Bend.

THE BABE COMES TO SOUTH BEND

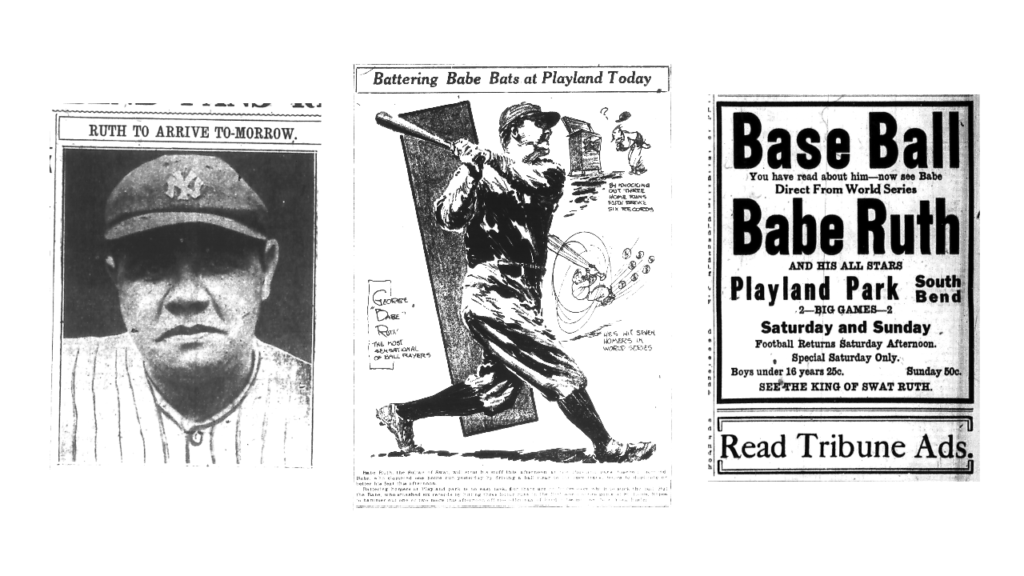

It wasn’t even two weeks after the dust had settled on the 1926 Major League Baseball season that the advertisements appeared in publications all over South Bend. Babe Ruth and His Big League All Stars were coming to town for a two-game tilt against the South Bend Indians.

The games were to be played at Playland Park. Ticket prices were set at a dollar for adults and a quarter for children. The South Bend Tribune implored fans to spend the money and make the trip. After all, the article warned, this was the last chance to see Babe Ruth in his prime because… “Ruth, like all other things and persons, is getting old.”

This was just a pair of exhibition games, but Ruth’s team wasn’t quite the Harlem Globetrotters and the South Bend squad was far from being the Washington Generals. In fact, the South Bend team featured a future Hall of Famer of its own – second basemen Freddie Lindstrom – as well as a future 200-game winner in Mishawaka native Freddie Fitzsimmons.

As for Ruth’s team, well they had Babe Ruth. The rest of the All Stars were actually a handful of big league also-rans and a smattering of players from lower level East Coast affiliated ball. The All Stars had a little more prestige than most of the rest of the South Bend team, but not much. Of course, the All Stars also had Babe Ruth at the peak of his powers, and that counts for something too.

THE LOUDEST HOMER IN THE HISTORY OF SOUTH BEND?

The first game was played on Saturday, October 23 in front of a sold-out crowd. While Babe Ruth and His All Stars were taking the field at Playland Park, the Fighting Irish were squeaking out a 6-0 victory at Northwestern, and a few of the louder ovations were reserved for the updates that were passed along the loudspeaker in between innings.

But the loudest ovations were saved for the Babe.

The South Bend nine actually held an early lead after a third-inning, inside-the-park home run by center fielder Canary Napier, but Ruth’s squad added runs in the fourth and fifth innings. By the time Ruth stepped to the plate with the bases empty in the sixth inning, his squad was already up, 6-3.

It was about to be more.

Babe Ruth dug his spikes into a batter’s box once located just outside the front doors of what is now a shuttered Walgreens at the corner of Lincoln Way and Ironwood. Then, with night hastening and the game about to be called for darkness, the Sultan of Swat turned on a 1-2 offering from South Bend’s Lefty Teague, and blasted a rocket over the right field fence toward the St. Joseph River. The South Bend Tribune located the ball on the Playland Racetrack, some 605-feet from home plate. There’s a young tree growing in a parking island at the IUSB student apartments at the place where the home run finally rolled to a stop.

Once he was around the bases, Ruth sought out a young fan, and gifted his bat – one that he’d used during the World Series! – to a six-year-old Thomas Hoban. After that, the umpire waved his arms and called the game on account of darkness.

Babe Ruth and His All Stars had taken the first matchup by a score of 7-3.

WINTER COMES EARLY, JUST LIKE IT ALWAYS DOES

If it’s at all possible, Sunday’s contest was even more hotly anticipated than the first one. For one thing, the South Bend team was trotting Freddie Fitzsimmons – a real big league pitcher – out to the mound. But for all of the fanfare that accompanied South Bend’s starter, there was even more excitement for the visiting hurler. That’s because Babe Ruth – more than five years removed from his last big league pitching appearance – would be taking the pill for the All Stars.

There was just one problem. A cold front had come through overnight, accompanied with drizzle and high winds. It was an unpleasant day for baseball, and only a few hundred fans showed up for the game. But to his credit, the Bambino made sure the game went on and he made certain all of the fans in attendance would see a show.

There were none of the fireworks of the previous day, but even without the home run, Babe Ruth was still a spectacle to behold. He lacerated a pair of singles and added a towering double over the course of four at-bats. On the mound, he scattered seven hits and allowed three runs. Fitzsimmons went pitch for pitch with the Babe, scattering seven hits of his own, and allowing the same number of runs.

By the time the game was called on account of rain in the eighth inning, Napier was wearing a topcoat in the outfield. The contest would go down in the box score as a weather-shortened 3-3 tie. That brought an end to the Bambino’s tour of South Bend and brought the curtain down on the season for the Indians.

The Tribunes coverage of the game concluded thusly:

“There will be no more baseball at Playland Park until the robins are twittering next spring.”

MISSING TREASURES

It’s been nearly 100 years since the Colossus of Clout christened South Bend was his 200-yard bomb, and outside of the microfilm, there’s not much in the way of artifacts that help tell the story of the playing of the game. There’s no record of what happened to the ball, and given the time, it wouldn’t be unheard of for the thing to have been collected and reused later that game.

None of the local newspapers dispatched a photographer to the contest, and it would appear that there are no photos of the Babe in action. Souvenir scorecards have been lost and discarded, perhaps faded into nothingness in shoe boxes in forgotten corners of attics.

But there is one thing and it’s still out there somewhere.

That bat.

I spent an inordinate amount of time trying to find that bat. Spoiler alert: I never did. I tracked down little Tom Hoban’s granddaughter in Cincinnati only to learn that, according to her uncle, the bat passed from Tom to his cousin Maurice later in his life. But when I reached out to Maurice’s kids, they knew nothing of the bat and had in fact never heard the story before.

In the end, it turns out there’s still a bit of mystery around Babe Ruth’s appearance in South Bend. That shouldn’t be surprising. It’s the presence of those tiny little mysteries that turn a story into a legend, and Babe Ruth stories tend to wind up as legends pretty quickly. It’s also why I spent six weeks of my life researching a home run that never, ever counted – because it’s fun to think that for as much ink has been spilled for Babe Ruth, there are still a few things left to learn.

Do you know anything about Babe Ruth’s missing bat or about his two-game appearance in South Bend? Please reach out to [email protected].