I’ve had time to catch up on my baseball card collection, and that’s how I got reacquainted with John Ellis.

Like most baseball fans, I have a favorite player or two. For the years I collect — basically from 1973 until the present day — my favorite is Rod Carew. He was smooth, a master of bat control. On a road trip in 1980, I watched him go 8-for-13 in a three-game series in Fenway Park, slapping line drives inches to the left or right of infielders’ gloves.

A favorite player, yes, but not favorite card. In my collections, Carew would be just one of 660 guys in plastic sheets in a binder, no better or worse than Dick Drago or Scipio Spinks.

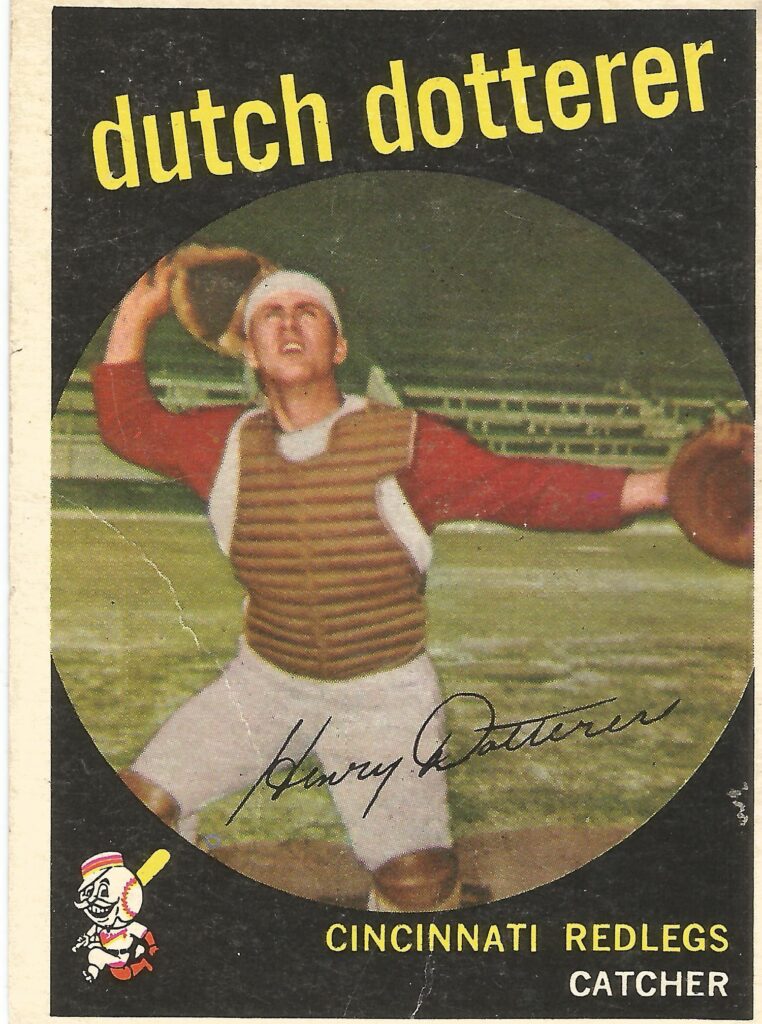

My all-time favorite card is the 1959 Topps card of Dutch Dotterer, a catcher for Cincinnati and the Washington Senators from 1957 to 1961.

For one, it says he’s a member of the Redlegs team. People were so worried about communism 60 years ago that they stopped calling the Cincinnati team by its traditional name, the Reds.

Also, the posed picture of him is amazing. He has removed his facemask and is searching the skies for a pop foul. Behind him, the bleachers are empty and the heavens are dark. All that matters is catching this imaginary ball.

His stamped autograph on the front of the card shows that he preferred his given name, Harry.

I’ll never have a complete 1959 set. I saw one recently on eBay recently offered for $1,500, but sets in better condition commonly sell for $5,000 or more. Card No. 288, Dutch Dotterer, with his five career home runs in 107 games, would cost me $5.

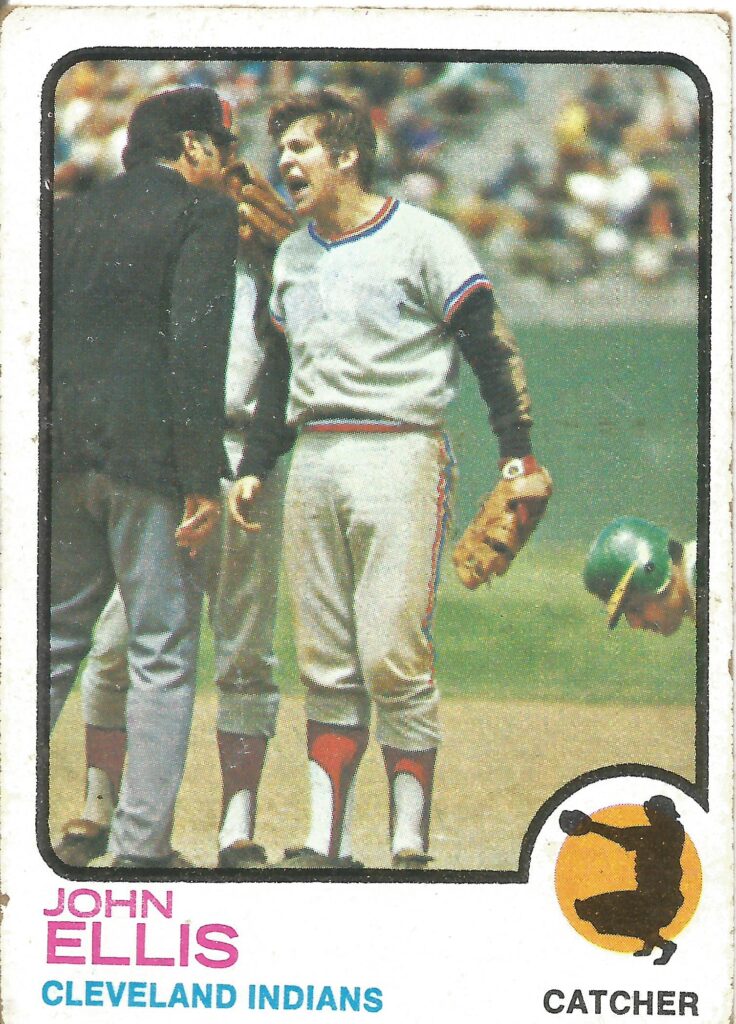

The John Ellis card I’m looking at today is from my oldest complete set, the 1973 Topps. If my house burns down and I need to replace that card, I could get it for $1.30. But I might just choose to leave his spot blank.

His is one of my least-favorite cards, and it has nothing to do with his baseball career.

Ellis was a phenom from New London, Connecticut. Signed by the Yankees in 1967, he soared through the Rookie and Class A leagues. By 1968, in just his second year of pro ball, he was called up to Class AAA, where he batted .348 in 13 games in Syracuse. He had a .333 average in 38 games at Syracuse in 1969, when he was called up to the majors.

At age 20, on May 17, 1969, he found himself as the starting catcher in Yankee Stadium. In that first start behind home plate, he caught a two-hit shutout by Stan Bahnsen. He was hit by a pitch from the Angels’ Tom Murphy in the third inning, his first major league at-bat.

He grounded out to short in the fifth and hit a sacrifice fly to center in the sixth. In the eighth, with the Yankees ahead 5-0, he hit an inside-the-park home run to center against Bob Priddy.

Imagine how that felt.

But also debuting with the Yankees later that year, on Aug. 8, was Thurman Munson. He beat out Ellis to become the everyday catcher in 1970, earning Rookie of the Year honors. He was a stud. Munson played in seven all-star games and was the league’s Most Valuable Player in 1976.

Meanwhile, Ellis played a little at first and third base while backing up Munson for three years. For the 1973 season, his Topps card shows him as a catcher for the Cleveland Indians. He was the starter there for three good seasons before he was traded to the Texas Rangers. He had six seasons in Texas before he was released just before Opening Day 1982.

He ended up with 13 years in the big leagues. He had a nickname, Moose, and had caught a no-hitter thrown by Dick Bosman in 1974.

I have no reason to feel sorry for Ellis except for that 1973 Topps baseball card. In it, he is about a foot away from an umpire and appears to be arguing a call.

Frankly, that’s not a good look for anyone. And it reminds me, unfortunately, of me.

I’ve taught myself over the years that the joy of competition has little to do with winning or losing. You’re there to experience something fun, a game with people you know. Still, about once a season, I find myself about a foot away from a softball umpire.

It usually starts with me politely telling the umpire he missed a call. If he doesn’t respond, I’m wondering if he heard me, so I step a little closer and speak a little louder. I choose my words carefully so he’ll get the full effect. He needs to know that, even if we’re losing 11-2, one strike or one out is crucial in senior citizen slow-pitch softball in small cities in Indiana.

This speech consumes 10 meaningless seconds of my life.

In 883 major league games, Ellis was ejected by umpires five times. If life were fair, the 1973 Topps set would show Ellis sliding into home at Yankee Stadium with an inside-the-park homer or catching the final pitch of a shutout. At the very least, he could be dramatically catching an imaginary pop foul in the darkness of an empty park.

If it were my own personal card, I wouldn’t expect heroics. It could show me pushing wheelbarrows for charity, unloading the dishwasher without being nagged, or picking up the dinner tab and tipping my server 30 percent. These laudable acts barely resemble a red-faced 67-year-old man insulting an umpire.

Sad to say, someone else takes the picture, and that’s what people keep for years to come.