Dan Badur tumbled out of a tree when he was 15 years old. A broken limb was the reason; a broken neck was the result.

He probably had a lot of broken dreams, too, after that nightmare fall that left Dan a quadriplegic for the rest of his life. “Well, I guess I may have really done it it this time,” he said to his mom, Barb Badur, while they waited for the ambulance.

“I told him that he was still talking and that meant he could use his head,” Barb later admitted.

And that’s what Dan did. He became a program analyst, a web designer, a township trustee and an inventor of a fishing rig for paralyzed people during his next 43 years.

Dan, the youngest of the Badurs’ three children, died Monday, Nov. 22, at the age of 58 after complications from a stroke.

His longevity is a testament to his own unflappable spirit and his mom’s full-time devotion to him, which started each morning before 5 a.m., when she would wash and then feed him.

Simple people. Amazing people. Inspirational people.

I knew that about them first hand.

For several years and a couple of times a week, I would relieve Dan’s dad Jerry, a retired South Bend firefighter, from his job of getting Dan out of his bed and into his wheelchair. Then locking my arms under his armpits, I would lift him up a dozen or so times to stretch out his back.

But sometimes, pressure sores developed on his lower back and would keep him in bed until they healed. It could be days. It could be weeks.

I never heard Dan complain. I never heard Barb complain, either. Sometimes, Jerry, who died eight years ago, would make light of their situation by referring to Dan’s fall as “the day Dan decided to play Tarzan.” Dan always had the appropriate comebacks.

If they had strong backs, other neighbors, friends and family members helped get Dan in and out of his wheelchair over the years. Yet it was Barb who was always there, taking care of her son. Now 83, she gave Dan comfort and hope hour after hour, day after day.

The Badurs made sure Dan got out and about in their converted van that accommodated his electric wheelchair. He had just enough movement in one hand to work the wheelchair’s controls.

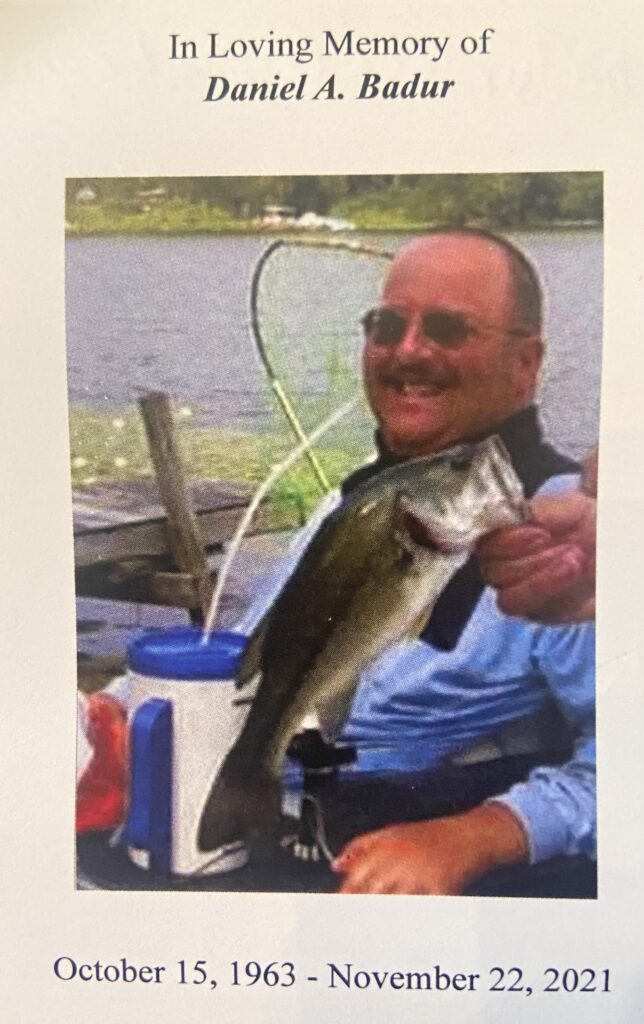

Their family’s fishing holiday up in Michigan was his best time of the year. His buddy, JIm Meckley, would bait and cast Dan’s pole and then Dan could control it with his head by a special contraption built into his wheelchair. A 9-pound bass he caught still hangs in his bedroom.

For more than a dozen years, Dan was able to work outside the home at Honeywell as a computer programmer analyst. He used a mouth stick to type on his keyboard. HIs mom went in to feed him lunch but eventually his co-workers decided they could take over that duty.

Dan brought them doughnuts on the 20th anniversary of his accident. “You just have to laugh sometimes,” he said.

He enjoyed being around people and staying in touch. He never missed sending my wife and I birthday cards and holiday greetings that he would create on his computer.

Dan lived in the Badurs’ back room where he had unbelievable collections of fishing lures, miniature race cars and unique beer cans.

When the weather was cooperative, he loved being outside in his wheelchair. He would sit in the driveway with a smile on his face and a straw hat on his head. If I was passing by on my bike, I would stop and visit — always enjoying our conversations.

A couple of years ago, some buddies and I tore down the Badurs’ old chicken/pigeon coop for them. Dan was going through another period when he was bed-ridden. All the guys went in and wished him well.

That was the last time I saw him. I wish I had been a better friend to him in recent years.

In his obituary, Dan’s paralysis wasn’t mentioned. He obviously didn’t want his life defined by his limitations. He had a saying he tried to live by: “Yard by yard, life is hard. But inch by inch, life’s a cinch.”

Life, of course, was hardly a cinch for Dan. Yet by all measurements, his was a meaningful one.